In recent years, few acronyms have stirred as much debate and contention in India’s landscape as ‘PMLA’ and ‘ED.’ The surge in the cases registered under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), by the Enforcement Directorate, has sparked intense scrutiny and criticism, prompting a closer examination of its legislative trajectory and implications for justice and governance. This article embarks on a journey through three distinct phases of the PMLA’s evolution, shedding light on its genesis, amendments, and unchecked authority.

Phase 1: The Inception (2002-2012)

The PMLA’s origins trace back to a meticulous legislative process spanning several years. Initially conceptualized as a tool to combat the generation of illicit wealth from serious crimes, its journey began with an inter-ministerial committee tasked with crafting an anti-money laundering law.

On 4 August 1998, the PMLA Bill was presented in the Lok Sabha. It progressed to the Standing Committee on Finance, which delivered its findings to Parliament in March 1999. With the dissolution of the Lok Sabha, a new iteration, the PMLA Bill 1999, emerged, incorporating numerous Committee recommendations. This version passed the Lok Sabha and was then referred to a Select Committee by the Rajya Sabha on 8 December 1999. The Select Committee issued its report on 29 August 2001, proposing amendments later integrated into the bill. Following further review, the amended bill gained parliamentary approval by November 2002 and was published in the Gazette on 17 January 2003. However, it wasn’t until 1 July 2005 that the bill’s provisions were enacted.

So, the PMLA has clearly had a tumultuous journey right from its inception. It emerged embodying a ‘serious crime’ approach, as is evident from the initial PMLA bills, the two committee reports, and the debates surrounding them. The law was aimed at targeting specific grave offenses but despite its noble intent, its early years witnessed challenges and critiques regarding scope and application. Concerns arose over the inclusion of relatively minor offenses within its ambit, prompting calls for refinement and clarification. However, the foundational principles of the PMLA remained intact, reflecting a steadfast commitment to curbing serious financial crimes.

Phase 2: The Unserious Anti-serious Amendment (2012)

The second phase of the PMLA’s evolution marked a significant departure from its original intent, as was widely feared. Amendments introduced in 2012 heralded a paradigm shift, diluting the threshold for what constituted a ‘serious crime’ and broadening the law’s scope. The blatantly obvious arbitrariness caused by the 2012 amendments to the PMLA resulted in the Supreme Court of India striking down the bail clauses in 2017. But the Parliament was quick to respond— no, not by restricting the stringent bail regulations solely to allegations that emanated from serious crimes, rather, it did away with the serious crime logic altogether when it came to bail. It was argued that all money laundering was grave, and that there was no reason to have a classification based on the severity of the crime.

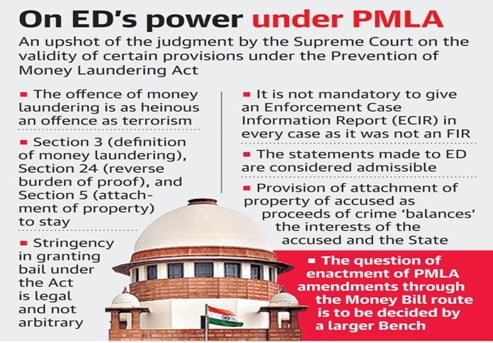

Retrospective application further extended the reach of the PMLA, encompassing a wide array of offenses beyond the initial purview. Driven by international pressures and the imperative for compliance, the amendments overlooked the ramifications for due process and individual rights. The once-discerning line between serious and minor crimes blurred, casting a shadow over principles of justice and fairness. When the legality of the amended clause was examined by the Supreme Court in 2022, it accepted the government’s argument, but the coercive nature of the law’s provisions still came under scrutiny.

Phase 3: Unchecked Authority of the PMLA and the ED (2012-Present)

In its current phase, the PMLA stands as a potent symbol of unchecked authority and institutional overreach. Empowered by expansive jurisdiction and coercive provisions, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) wields considerable power in invoking the law against perceived offenders. Be it the very strategically timed summons issued to two Dalit farmers hailing from Tamil Nadu – regarding a case that was more than four years old and for which they had already been acquitted, or the opportunely timed arrest of the sitting Chief Minister of the capital of the country (in the first time that a sitting CM is behind bars), these instances are equally alarming, in that they underscore quite expansively, the two possible extremes of the law’s far-reaching implications and its (quite possibly) limitless potential for misuse.

This transformation of the PMLA into a tool of coercion has sparked widespread concern and debate. Critics argue that its overzealous application undermines fundamental rights and democratic principles. The disproportionate impact on individuals caught in its legal net, coupled with a lack of accountability and oversight, raises urgent questions about the balance between security and civil liberties. On the surface, the PMLA is a legislation enacted by the Government of India to prevent and combat money laundering and related offenses. It provides a legal framework for the detection, investigation, and prosecution of money laundering activities with the aim to curb the generation of black money and the financing of illegal activities. However, as is clearly apparent, all is not so simple and well.

Thus, the evolution of the PMLA unfolds as a cautionary tale of legislative ambition and unintended consequences, or perhaps maliciously intended consequences. What began as a targeted measure to combat serious financial crimes has morphed into a sprawling apparatus of state power, with far-reaching implications for governance and justice. As we confront the challenges posed by the PMLA’s evolution, it is incumbent upon us to recalibrate its provisions and restore balance to our legal framework. Only through vigilance and reform can we ensure that the pursuit of justice does not come at the expense of individual rights and freedoms.

Yash Mittal is a student pursuing Economics Hons. from Jamia Millia Islamia.

Edited by: Mukaram Shakeel

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings