The invisible wounds of Kashmir valley go beyond conflict, shaping minds in silence. In the Kashmir valley and border towns like Uri, Poonch and Rajouri, neglect of mental health leads to severe trauma. With no awareness, counsellors or therapy these wounds deepen, demanding urgent care, compassion, and mental health awareness.

“muskrata hua chehra kuch aur bataya karta hai

Dil mein rakhe zakhm paharon jaise hua karte hain”

The Smiling face says something else entirely,

While wounds buried in the heart are deep like mountains.

~Mobashar.

Introduction:

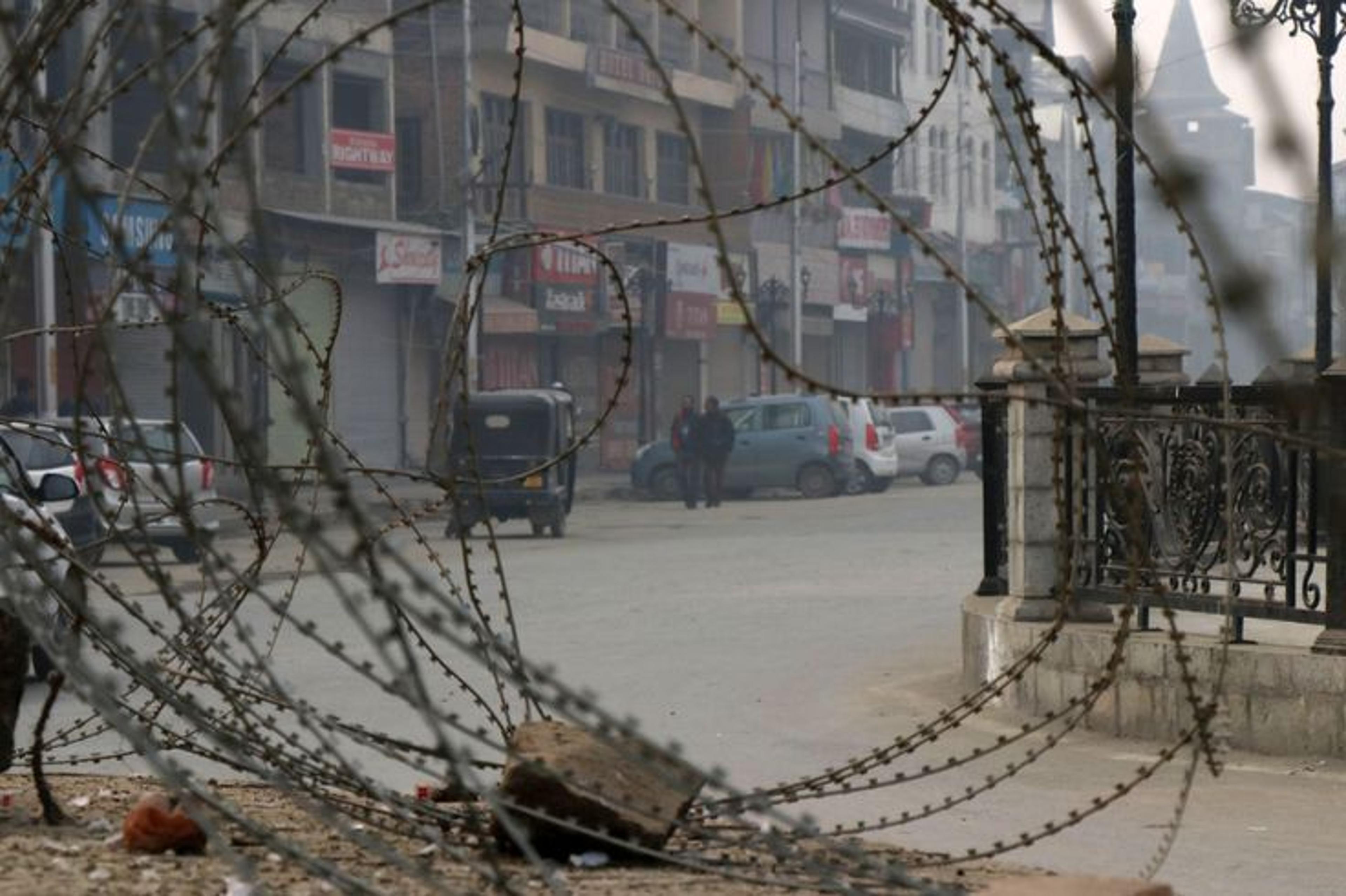

In the place where mountains stand silent and the air carries the story of endurance; many hearts silently collapse under the weight of invisible burdens. In Kashmir, the wounds of conflict are not only carved into the land but deep within the minds of its people.

Why Mental Health in Kashmir Needs Urgent Attention?

Mental Health in Kashmir demands urgent attention due to the region’s prolonged exposure to conflict, socio-political instability and natural calamities. The cumulative effect of these factors has created a mental health crisis that is both deeply rooted and dangerously overlooked.

Kashmir has been a conflict-ridden region for over three decades. Constant exposure to conflict encounters has deeply scarred the collective psyche of the Kashmiri population. In Kashmir, conflict is not a distant event but a lived experience. Encounters between militant and security forces often erupt within residential areas, leaving behind not just physical destruction but long-term emotional and psychological trauma.

Mental illness is stigmatized in Kashmiri society, which prevents individuals from seeking timely help. Many families hide the mental health issues of their loved ones due to shame or fear of social exclusion (Medecins Sans Frontiers, 2015). This leads to delayed diagnosis, worsening of symptoms, and in some cases, suicide.

In Kashmir, there is a severe shortage of trained mental health professionals. The entire region has only a handful of psychiatrists and clinical psychologists, mostly concentrated in urban centers like Srinagar. Rural areas remain largely neglected. Meanwhile, the mental health services in primary healthcare are almost non-existent.

The Psychological Impact of Conflict

For decades, Kashmir has witnessed a cycle of unrest, uncertainty and unresolved trauma. Whether it’s a shutdown or an encounter, each incident leaves behind fractured minds. The people, especially the youth, live in a constant state of hyper-awareness, fearing what might happen next.

In Kashmir, and particularly in border areas like Poonch, the deepest wounds are often carried silently within the mind. The sounds of gunfire, curfews and breaking news alerts are not just events, they become psychological triggers that disrupt sleep, concentration, and emotional stability.

The constant fear of loss, the unpredictability of violence, and the feeling of helplessness have given rise to a chronic state of anxiety among the people. Even in moments of peace, many live with subtle tension, always bracing for the next incident. This form of anticipatory trauma affects both the young and old, slowly eroding mental resilience.

This is the invisible cost of living with uncertainty, something many Kashmiris and residents of border areas like Poonch, Rajouri, Uri and Kupwara carry in their minds like quiet burdens. In the valley and the border areas, where the conflict often replaces calm, mental health has long been neglected. While the world sees the headlines, few recognize the psychological wounds left behind.

What Does the Data Say?

Over the years, multiple studies have highlighted the psychological toll of conflict on the people of Kashmir. The numbers are alarming, and they confirm what many people, especially in regions like Poonch and Rajouri experience daily.

Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), 2015:

A landmark study conducted in 2015 by Medecins Sans Frontieres in collaboration with the Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (IMHANS) and University of Kashmir, found that:

45% of adults in the valley showed signs of mental distress.

41% had symptoms of depression.

26% showed signs of anxiety.

19% met the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

These findings highlight that the mental health crisis is not limited to a few individuals, it is a community-wide phenomenon, especially in areas exposed to frequent conflict.

Government Medical College (GMC) Srinagar, 2020 – Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21):

During the Covid-19 lockdown in 2020, a study conducted by Government Medical College (GMC), Srinagar, using the DASS-21 Scale, reported that:

53% of respondents experienced depressive symptoms.

38% showed signs of anxiety.

24% reported stress-related disorders.

Researchers have also pointed out the intergenerational nature of trauma in the valley, where children grow up in an atmosphere of fear, silence and loss.

Collective and Intergenerational Trauma in Kashmir

Trauma in Kashmir does not exist in isolation, it is shared, inherited, and deeply embedded in daily life. While one person may carry immediate memory of a violent event, another carries its emotional residue. This gives rise to two profound psychological realities – Collective trauma and Intergenerational trauma.

Collective trauma refers to psychological damage experienced by an entire community or group due to shared experience of violence or chronic fear. In Kashmir, decades of Armed conflict, surveillance, disappearances, lockdowns and political instability have shaped a collective emotional landscape.

In Kashmir, trauma is not personal, it’s collective. In such an environment, mental distress becomes normalized, and suffering becomes silent and collective. This makes it harder for an individual to recognize when they need help, because the pain is widespread and often unspoken.

Intergenerational trauma refers to psychological suffering passed down from one generation to another, not just through stories, but also through behaviors and emotional patterns.

Children in Kashmir often grow up hearing about or witnessing violence, loss and helplessness. They may not fully understand what happened, but they absorb insecurity about the future, fear and anxiety from parents.

Psychologists like Yael Danieli and Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart have theorized how trauma can transmit emotionally and behaviorally through generations, especially in communities facing prolonged violence.

In the Kashmir valley, trauma moves silently through families, conversations, and even bedtime stories. In border areas, where the echoes of conflict reach every household, children often carry the emotional weight of their parents’ suffering.

Conclusion

In Kashmir, pain often walks in silence. It doesn’t always scream or cry out. It hides behind smiles, behind normal conversation and behind the silence after a breaking news alert. From Srinagar to Poonch and from Uri to Anantnag, the burden of unhealed wounds weighs on minds that have learned to survive, not to speak.

As a psychology student and as someone who belongs to this land, I know that true peace cannot come through politics or policy alone. Peace must begin in the mind, with acknowledgement, with conversations and with care.

The time has come to treat mental health as a right, not a privilege and to place counselors in classrooms. And it’s time to open our clinics to therapy, not just to medicine, to listen deeply to the pain people carry in their silence. This is because healing Kashmir means healing its people, and healing its people means starting with minds.

Sayed Mobashar Ali, the guest author, is pursuing Psychology from Jamia Millia Islamia

Edited by: Sharmeen Shah

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of TJR.